- The skills trap standing in the way of agri-processing success in Africa

- A supportive ecosystem and support services for African agribusiness

- Resilience: Navigating Environmental and Operational Challenges

- Conclusion: persist and thrive

"Why is running factories in Africa so challenging?" This is a question I often encounter from impact investors and entrepreneurs on the continent. We are all familiar with stories of food factories shutting down or ceasing operations. Having been involved in running factories for fourteen years in Africa, we've faced many obstacles ourselves and had to overcome numerous operational hurdles. We also made mistakes and had to revisit our strategies more than once. This article will delve deeper into the challenges of agri-processing in Africa, offering insights from firsthand experience.

The type of business we’ll be discussing is an SME. These businesses are often run by a founder or a small team with a turnover between $2 million and $20 million. They are not yet capable of realizing the full benefits of economies of scale or the resilience of larger businesses.

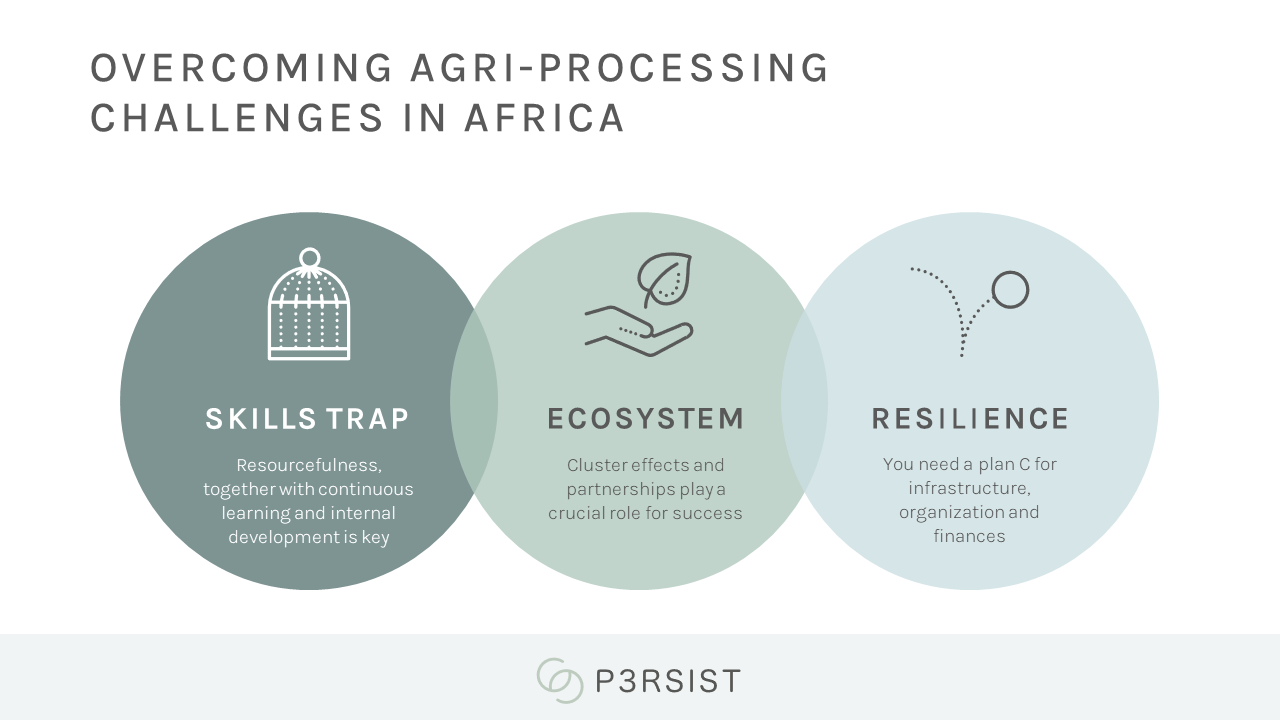

We’ll explore three main themes: the complexity of skills required to run a successful agri-processing business in Africa, the role of the manufacturing ecosystem, and the strategic role of business resilience. This article is not intended as a scientific exploration but as a recount of our firsthand experiences. Even though we have written it from the perspective of manufacturing, much of this article would also apply more generally to doing business in Africa.

The skills trap standing in the way of agri-processing success in Africa

Success in agri-processing requires a sophisticated skill set that is difficult to cover with a small team. This creates what could be termed an SME manufacturing skills trap.

Top skills required for agri-processing success in Africa

As far as we are concerned, the top five skills are the following:

Quality Management

Lean manufacturing and advanced food safety certifications, such as the British Retail Consortium Global Standard (BRCGS), are essential. While HACCP and just-in-time receive most of the attention, success in quality and food safety is really about business culture. Few people in local labor markets have experience with this sort of culture, and it takes years to build.

Food Plant Engineering Systems

Compressed air, pressurized steam networks, electrical installations, and sorting technology are highly specific and usually imported. A major challenge is keeping the equipment operational once the installation engineers have left.

Information Technology

The accuracy, completeness, reliability, relevancy, and timeliness of information are greatly enhanced through technology use, and we would argue that systems such as traceability, inventory and cash control, process control, and HR systems would be practically impossible without it. Technology also helps leverage your scarcest resource: management time. In a separate article we argued that mastery of employee integrity challenges is a precondition for success in Africa and we strongly advocate the use of technology to help achieve this (read the blog here: Enhancing Employee Integrity in African Agribusiness).

Financial Acumen

It’s not just about being able to produce financial reports like P&Ls and balance sheets. In our experience, there are very few factory managers who can quantitatively state what the impact of a 1% change in a key production metric would mean for the bottom line. That is dangerous. You need to know which levers to adjust on the factory floor to drive results.

Leadership and Communication

Uncertain environments require flexible leadership and rapid decision-making. This necessitates the ability to make decisions in the heat of the moment that align with the business strategy and its critical success factors. Additionally, dealing with international shareholders, local labor unions, smallholder farmers, government officials, European clients, and employees from very different backgrounds requires advanced cross-cultural leadership skills.

The Skills Challenge for African agribusiness

Local labor markets with expertise in the five skills in the context of an agri-processing facility are shallow and, in some cases, non-existent. Where do you find your local BRCGS specialist when there is not a single other BRC certified business operational within the country? Where do you find the staff to maintain that piece of equipment of which you are the sole operator in a country? Who can not just maintain your server and SQL database but continue to improve on it?

It gets worse: midsize businesses need all these five skills to be successful but do not yet have the capacity to hire specialists for each field. They need to find people who have mastered several of them to function. This becomes an even harder job to do. Hence the skills trap of medium-size agri-processing. In practice, one to three of the five essential skills are not well covered, and this risks becoming the stumbling block that has the potential to kill the business.

Strategies for overcoming the skills trap in African agri-processing

There are no obvious answers to the skills trap; otherwise, it would have been fixed already. Bootstrapping is the only way forward until you have the scale to hire specialists. In practice, this means that businesses with highly analytical leaders, problem-solving skills, and resourcefulness make it to the next level. If I were in charge of making investments into African agribusiness, resourcefulness would be the single most important characteristic I’d look for in senior management before making an investment. What do we understand under resourcefulness? One of the most useful definitions comes from the topgrading system for hiring high performers:

“Resourcefulness is a combination of drive, passion, analytical ability, decision-making, perseverance, resilience, and energy that, when applied, snatches success out of the jaws of defeat. Resourcefulness is figuring out how to get over, around, or through barriers to succeed, and then doing it. Resourcefulness is the opposite of coasting along, giving up, running to bosses to solve problems, whining, making excuses, and then giving up some more.” Source: Topgrading.

Here is how we approach the process of getting out of the skills trap. The key is to identify people with high levels of resourcefulness, promoting or recruiting them, and teaching them the essentials of whatever technical field we needed to develop. Yes, this does mean that you must first learn this yourselves. Use books, YouTube videos, MOOCs, or whatever you have available to learn about a certain field. If you want to become successful, you must develop broadly and be conversant with a multitude of topics relevant to your business. Leaders are readers.

Within the organizations where I worked, there were always rough diamonds working on the factory floor: people with great talent but without the opportunities that I had had to get an education and develop expertise. With the right identification, personal development plan, and tools, these people were capable of going really far. I’ve worked with a production manager who had never finished high school; I had an HR manager who started on the factory floor, studied in his free time, sponsored by the organization, and eventually completed a master’s in law, and many other similar examples. People whom we have helped to develop, regularly went on to start their own businesses or take up positions of responsibility in other organizations. The in-house development of resourceful people is key to bootstrapping the organization out of the skills trap.

On a side note, I think that there are opportunities for technical assistance funds, NGOs, and donor-funded value chain development projects to do a better job in resolving the challenge of the skills trap. Usually, these facilities look for projects of around 12 months that provide some tangible results so that these funds can report back to their donors how many people were trained, etc. I think that much more attention should go into resolving this skills trap in agribusiness SMEs, even if that means paying a highly experienced maintenance manager for two years. We need a more long-term approach, targeting specific bottlenecks.

A supportive ecosystem and support services for African agribusiness

You’ll need a manufacturing ecosystem for your processing plant to be successful. The manufacturing ecosystem has the potential to alleviate some challenges of the skills trap or to make it worse. Too often I see location choices being influenced more by proximity to raw materials rather than access to specialized services.

Elements of an Effective Agribusiness Ecosystem

Here are a few examples of ecosystem factors you could consider:

- Specialized workshops. Think rewinding of electrical motors, welding of stainless steel, calibration of scales, compressor maintenance, IT infrastructure maintenance, boiler refractory repair, that sort of thing.

- A talent pool for your staff, particularly middle management. If there is no quality local school, it will be so much harder to get quality management to live nearby.

- Logistics service providers: local transport, customs clearing, international shipping, etc. (a key consideration is having your imported critical spare parts cleared fast).

- Access to laboratory testing services for the water you use in manufacturing and for your export requirements. You’ll need a lab for every shipment of food items to the EU, for example.

- Training services: you’ll want to train your staff in manufacturing excellence, health and safety as well as firefighting and emergency drills. These are not one-off but recur at least annually.

- Specialized hardware stores: having rapid access to spare parts through local hardware stores can be a lifesaver.

- Professional services such as bankers, lawyers, accountants, and recruitment agencies.

- Waste disposal services.

The above is a list of elements of an ecosystem that you’ll need just to keep you going. The higher the levels of expertise of your service providers, the easier it will be to overcome shortcomings in your own organization. Apart from having access to services, you will also want to build knowledge, innovate and pass certifications. Here you’ll need to focus on partnerships and transfer of knowledge. Without aiming to be exhaustive, here’s some points to consider:

- Food safety professionals and trainers

- Industrial engineers

- Implementation partners

- Certification bodies

- IT consultants

How location choice influences Agri-processing success in Africa

Too often inexperienced processors come up with location choices that reduce their chances of success. Building an agri-processing plant in a rural area, two or three hours away from the nearest serious town might get you applause from impact investors but it’s a really poor choice if you’re aiming for success in the long term.

You’ll struggle to find qualified middle management, getting an emergency spare part will take you a full working day instead of an hour or two, waste disposal services might be non-existent and service providers will either not service your area or charge you hefty bills for transport, accommodation, and sitting allowances.

If there’s one take-away from this, it is that remoteness exacerbates the skills trap. You’ll need to know even better what you’re doing and you’ll need a considerably higher level of skill. Choose your location so that your life becomes easier, not harder. Beneficial cluster effects are real.

Development of partnerships to thrive

The key for long term innovation and advancement of knowledge and skills is partnerships. You’ll need long-term partners that drive your food safety knowledge, food plant engineering competences, traceability advances, and (often overlooked) strategy, leadership, and management skills.

Sometimes the knowledge and expertise in your niche are next to non-existent locally and you’ll have to seek it abroad. NGOs, impact investors, and technical assistance facilities can be great partners. Develop relations with them early on, learn to speak their language and how to meet their project management and reporting requirements (something for a separate topic). This will set you up to accelerate your learning, gain skills and expertise faster, and have others participate in the cost, which can often be considerable.

Key takeaways for ecosystem and partnerships choice for African agribusiness

Make smart location choices when it comes to your manufacturing ecosystem. Pick a reasonably large town, preferably with an agro-industrial base already. There are huge benefits to be gained from cluster effects. Only deviate from this if you know what you’re doing and there are offsetting benefits to be gained from a remote site. Develop partnerships focused on knowledge transfer early on and acknowledge you’ll be in it for the long term. NGOs, impact investors, and technical assistance facilities can be a great help as long as you’re aware of their requirements and can meet them. Building the right ecosystem for your agro-processing business will set you up for long-term success.

Resilience: Navigating Environmental and Operational Challenges

Efficiency is important, but resilience is often overlooked in business plans focused on agri-processing in Africa. New factories are launched where the CAPEX budget is stretched to the limit to achieve economies of scale and/or efficiency, while resilience does not receive the attention it deserves.

Why Business Resilience is So Important for African agribusiness

Resilience is all about defending the bottom line. Small events have a big impact: if your scheduled processing covers 11 months a year (let’s assume one month for industrial maintenance), you’ll work 9 to 10 months to be able to pay your suppliers, your staff, interest, etc. The final one to two months is for your profit. You lose half your profit if you experience delays or standstills that accumulate to 2 or 4 weeks.

Losing a few weeks’ worth of production happens faster than you think. Remote and challenging environments tend to have a habit of throwing spanners in the works. Here are a few I experienced myself or saw elsewhere:

- Irregular water supply

- Coup d’états (we managed through two)

- Continued electricity outages for 12 hours a day

- Heavy rains make important supply routes unpassable

- A railway bridge that’s critical for your export route collapses

- The internet gets switched off during periods of social unrest

- A lightning strike on the electricity grid nearby blows up your transformer

- Diesel runs out because of maintenance delays at the monopolist fuel refiner in the country

- Severe undervoltage on mains electricity supply fries a third of electrical components in your machinery

- Your container with imported packing materials is held up at customs for two months for unclear reasons

- Your organic certifying body can no longer certify farmers because the security situation does not allow it

- The urgent spare part that you ordered by airfreight somehow takes fourteen days to arrive and get cleared

- The container with critical machinery that you ordered was “dropped” somewhere in the shipping process, rendering $150k of equipment useless.

- The farmer cooperative that you rely on for 30% of your raw material decides to start processing themselves two weeks before the buying season starts.

- The list goes on… but you get the idea.

The solution is designing for resilience: making sure you always have a plan C. We identify three sources of resilience: infrastructural, organizational, and financial. Let’s dive deeper into each of them.

Resilience of Infrastructure in African agribusiness

In challenging and remote environments, designing your food processing plant for resilience is key. These three points make industrial sites in remote locations vulnerable:

- Complicated logistics

- Lack of specialized hardware providers

- Distant technical support services

The main challenge: keeping things going when stuff (inevitably) happens. The key capacity you need to focus on is being able to bridge the time to fly in specialized technicians or spare parts to solve your problem. You need to have a plan C in place to keep going.

Design for redundancy. Some typical issues and observations:

Too many plants I’ve visited rely on a single steam boiler for their pressurized steam needs. If anything goes wrong (let’s say the pump or refractory wall), operations grind to a halt. Eliminate single points of failure.

Not checking the suitability of your equipment for the environment. The environment in Africa is harsh: high temperatures, lots of dust, high humidity, low humidity, bugs, and other pests. You wouldn’t be the first to end up with a compressor shutting down around noon because of the heat. Make sure you spend the money on equipment that is fit for purpose. Harsh environments demand adapted, better quality equipment.

Numerous processors do not have a workshop worthy of the name. Their maintenance teams are understaffed, and a spare parts store is nearly non-existent. This is a recipe for disaster. You need to have a workshop fitted with the tools capable of addressing a good chunk of emergency repairs. The maintenance department needs to be properly staffed.

Whereas in processing we work to eliminate variance, the environment is full of it. If you work with seasonal inputs, you need to plan for peak deliveries and the capacity to offload trucks rapidly. This requires overcapacity on offloading bays, forklifts, scales, etc. Another is storage capacity of finished product. Outbound logistics may encounter a snag, filling up your finished goods storage up to the rafters before goods start flowing again. Don’t let it stop production: oversize your storage.

For your machinery, ideally you’ll want to work with units of threes: three identical pieces of equipment, whereas production runs on two. This gives the greatest flexibility. You can rotate machine use and keep 100% of your production going on two machines whilst you service / maintain the third.

Of course, working with threes for everything is not always feasible because of CAPEX constraints. However, instead of purchasing one machine with a capacity of let’s say 500 kg/h, two machines of 250 kg/h are a superior choice. In case one of the machines is knocked out of production you’ll still be able to run at 50% instead of at 0%. If you supplement this approach with a strategic spare part reserve and some rapid technical intervention protocols, you can still have a very robust and resilient processing facility for only a marginal increase in capital outlay.

Resilience of the Organization in African agribusiness

Organizational resilience for agri-processors in Africa is just as important for long-term success as infrastructural resilience. I’m talking about your key people here.

For your organizational resilience, ideally, you’d want two persons to cover every key role: let’s say an IT manager and an assistant for all your IT infrastructure. Similar for food safety, engineering, etc. However, as a growing SME your budget may not support this. You know you’re vulnerable with just one person covering that field of expertise but how to deal with this?

Engagement. First, you need to make sure that these key people are happy where they are and that they have the direction required and the resources to accomplish their work. Make sure they have no reason to look for something else.

Don’t over-extend, limit your vulnerabilities. Do not launch simultaneous initiatives on IT, engineering, food safety, and traceability, for example. Focus on one field for a short period of time (around 6 months) and put your entire organization behind this effort. Make sure you get the staff you need as the initiative matures. You can have your high-performing specialist move on to a next initiative and train someone else to operate and maintain the newly acquired capabilities.

Cross-train your people: get qualified people from other departments involved. For example, machine operators on a specific type of equipment can be rotated to the next department to master a second piece of machinery. Having a pool of machine operators conversant on let’s say the top-3 of your critical and/or most complex pieces of equipment is invaluable. It will give you much more flexibility and it will be more enjoyable for your staff as well. If you want to dive deeply into cross-training your people, helping them master new skills fast, I recommend reading the book Training within Industry by Don Dinero.

Finally, getting each position covered by two persons is key to reducing vulnerabilities and improving your organizational resilience. This is one major benefit of economies of scale. Determine the required size of business that will be able to support double coverage for key skills and execute your strategy to get there fast.

Financial Resilience in African agribusiness

Apart from infrastructural and organizational resilience, financial resilience is another key factor in the long-term survival of African agri-processors. When an agribusiness goes out of business for financial reasons it generally looks like this:

- The promoter/founder blew all equity + a long-term loan on CAPEX, building the factory, and installing machinery.

- Working capital was an afterthought and new loans are required to cover operations.

- No financial buffer is in place to accommodate one or two bad years.

In this case, the balance sheet is highly leveraged, and any short-term imbalances in the markets for raw materials and finished product will lead to a default. And if I’ve learned one thing in fourteen years of agri-processing in Africa, it is that short-term market imbalances will play a big role in your annual financial results.

Then depending on the type of business there may be the following additional factors:

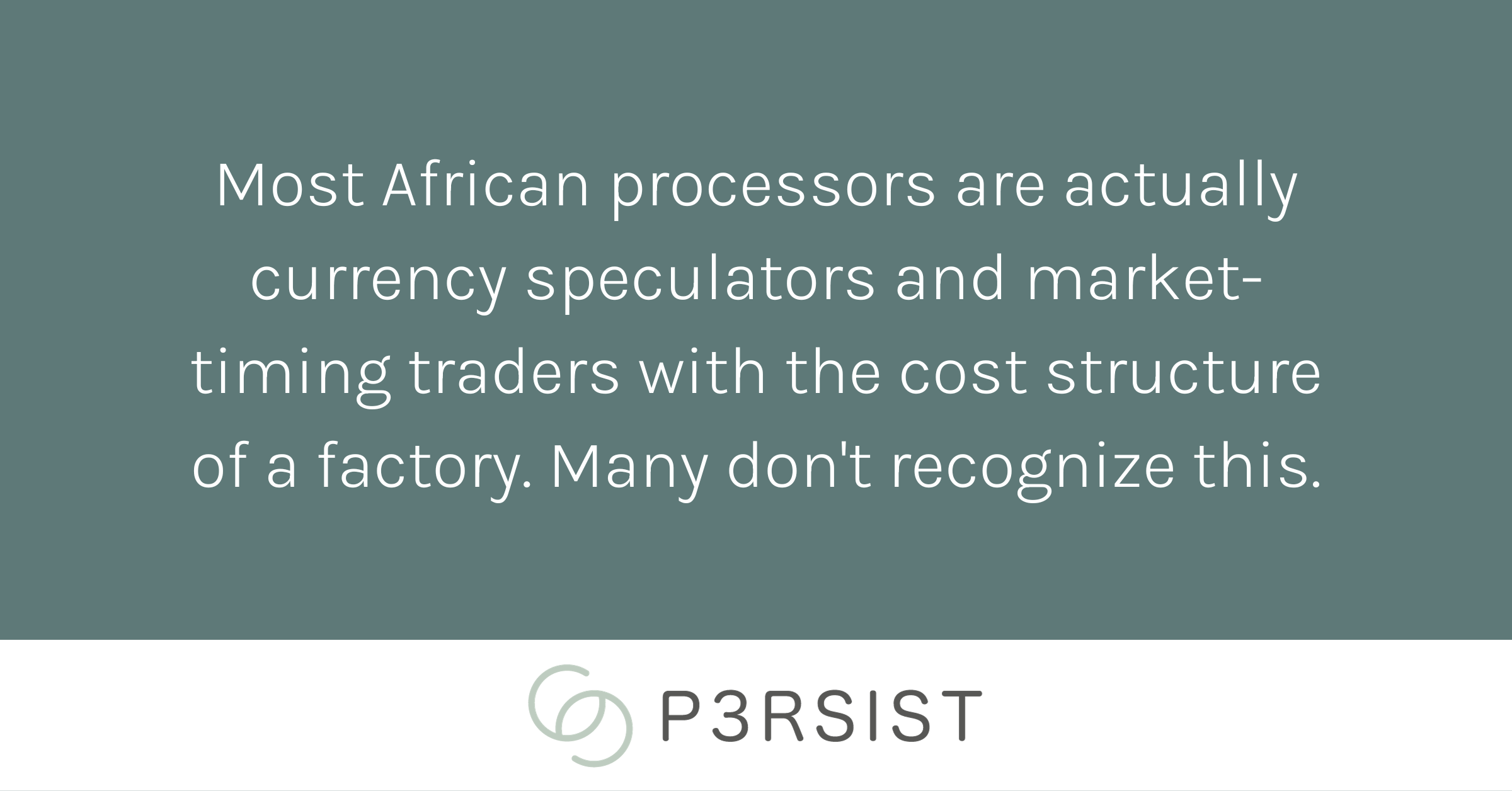

- The business buys agricultural produce during the harvest season and stores for year-round processing. The factory tries to market time both the purchasing of raw materials and the sale of finished product.

- The business buys raw materials in one currency and sells in another. This is typically the case for exporters. Currency exposure is not hedged.

These two factors add up to the company being essentially a currency speculator and commodity trader (without the required knowledge or experience) with the cost structure and CAPEX requirements of a factory. In this case, no matter how good you are at manufacturing, decisions on market timing and the currency markets will have a greater impact on your bottom line.

If you’re serious about processing you need to hedge the currency risk and forget about trying to time the market. You know that in the long run the price differential between finished product and raw material MUST allow for profitable processing. Without the networks and knowledge required for successful trading, it is a fool’s errand to try and time the markets (some very obvious cases exempted).

Make your life simple and focus on spreading out your purchases and sales over time so that you can get (as close as possible) to the market average. If you do this, you’ll do better than 80% of the processors who try to time. Then the true differentiator between your company and the next processor is your capacity to manufacture effectively.

If you do the above, you’ll set yourselves up for long-term success. In the short term, however, market imbalances are a reality and can negatively impact your bottom line for a year or two. You need to have enough financial reserves to make it through such a period. Make sure you have enough to fight another day.

Conclusion: persist and thrive

The journey of agri-processing in Africa is not an easy one but it’s precisely the challenges that also create the opportunities for growth and impact. Navigating the terrain requires making informed choices about location to leverage cluster effects, building a resilient manufacturing ecosystem, and forming robust partnerships that enhance knowledge and operational skills.

Resourcefulness and resilience are the cornerstones upon which successful entrepreneurs build their businesses. Both need to be embedded within the organization, from the development of a skilled workforce to the design of facilities capable of withstanding the unpredictable African operating environment. Financial liquidity, too, is essential to be able to withstand adverse conditions.

The skills trap, even though one of the most serious challenges, is not insurmountable. It calls for a bootstrapping attitude with emphasis on continuous learning and internal development. Companies investing in training and development will find themselves well equipped to thrive despite the challenges to African agri-processing.